Algeria, as other countries, has not been spared the consequences of the global pandemic caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. This global pandemic has deeply affected the socio-economic conditions of Algerians’ life, resulting in increased expenditure on healthcare and influencing income levels and consumption patterns within Algerian households (Ziar et al., 2022). With the spread of the pandemic across the country, the government implemented emergency policies to augment health sector expenses and to provide the required medical services to citizens. An emergency intervention For instance, total of 473.6 million USD were directed for medical supplies (World bank group, 2021).

A transformation of consumption practices has occurred among algerians in close association with the spread of of that global pandemic. Corona pandemic crisis Indeed, the imposition of sanitary confinement resulted at suspension of plenty socio-economic activities, that led in turn to deceleration trend across various sectors. The initial phase of the state of emergency which lasted for the first three months of lockdown (March, April and May), marked a substantial transformation in household consumption behaviors. During Also, a state of panic generated in the public space, particularly when it related to the access to essential foodstuffs (such as semolina and flour) and hygiene products. The fluctuation in the availability of these commodities within the market had resulted in a disruption in pricing, which in turn negatively affected the socio-economic stability of the Algerian families.

For more understanding to the socio-economic impact of the Covid-19 in Algeria, we designed this study aiming to examines the effect of that global pandemic on the consumption patterns of scholar’s category and in country. However, this category makes up the largest proportion of people in our sample, but not the entries part of it.

This demographic was chosen as the focus of our study due to its significant statistical representation within the dataset. The objective of the research is to examine the impact of the pandemic on consumer behaviour by analysing responses to changes in financial resources, food consumption, and cultural activities, including entertainment, cultural events, and media consumption.

This research is vital for understanding consumer behaviour and evaluating policy modifications that affect household resources during a pandemic. At the first we discuss the literature review, after we focus on the methodology of research, finally we analyze our results

Methodology

Theoretical approach

The phenomenon of consumption is subject that could be analysed and scrutinized through the lends of a multitude of theoretical frameworks. It is a socio-economic phenomenon that could be determined by plenty of factors including economic, social, and cultural determinants. According to neo-classical economic theory, consumption is defined as a rational economic activity involving the utilisation of goods and services to fulfil individual needs (Deaton & Muellbauer, 1980; Langlois & Cosgel, 1996) ). This process is articulated before the determination of the price structures of the products and services used, in the context of a goods market and in correlation with the income layers of individuals, families or households, as well as their corresponding financial plans (Bosserelle, 2017). Furthermore, behavioural economics introduces additional layers to this understanding by emphasising the role of psychological factors that would lead to deviations from rational decision-making including biases and heuristics that affect how consumers perceive values and make choices (Askari & Refae, 2019) .

Indeed, behavioural economics field discusses the complexity of consumtion as a phenomenon through illustrating various aspects including the decisions that have been formulated around the concept of relative rationality (Arninda et al., 2022; Simon, 1997). This concept is influenced by factors that are both endogenous and exogenous to the society. It is a perspective that is aligned with sociological frameworks of consumption, and which asserts the diversity of preferences in relation to social stratification and the symbolic significance of consumption practices (Bourdieu, 1993).

In the context of a global pandemic, a theoretical dimension must be incorporated regarding the notion of “crisis economies”, given that such circumstances precipitate extraordinary measures typically enacted by governments to uphold sustainable economic activity (Auzan, 2020). Such measures frequently comprise stimulus packages, alterations to fiscal policy, and interventions designed to stabilise domestic markets. These measures and policies can result in significant shifts in consumer behaviour and value perception.

Economies experiencing crises have often experienced a robust regulation of monetary policy by the government, coupled with economic plans that prioritize saving over consumption. This context of resource allocation is crucial for examining and understanding potential shifts in family consumption patterns (Baker & al., 2020; Irace & Lojkine, 2020). Consumers are modifying have modified their consumption behaviours based on rational decision-making, which is intrinsically linked to modifications within their surrounding environment (Kumar & Abdin, 2021).

However, these shifts may also reflect broader societal trends, such as increased awareness of sustainability and the impact of consumer choices on the environment. As families navigate these changes, they may increasingly seek out products that align with their values, leading to a rise in demand for sustainable goods and services. A tendency that encourage further the adaptation of, more sustainable practices, which in turn create a feedback loop that reinforces these consumer preferences and encourages innovation in eco-friendly product development (Herrero & al., 2023).

Consumption a reasonably subjective act

Consumption behavior, either in its collective or individual form, represents a crucial thematic of economic analysis. Taking the decision of consumption individuals have engaged in a rational selection process between the array of available goods and services, considering their associated costs (Arninda & al., 2022).

Income levels and budgetary constraints, are crucial determinants for understanding the consumption behavior. However, socio-cultural determinants are also significant in examining consumption phenomenon. The sociological approach focuses mainly on preferences, trends, and the dynamics of cultural influence, as well as on so-called positional purchases, which confer a form of social status upon the individual who possesses the consumed good (Beckert, 2009), he purchasing behaviour of consumers is highly subject to transformation in response to economic crises. However, the consumption patterns are also influenced by social and cultural contexts (Chikhi, 2021). This complex relationship between economic circumstances and cultural influences in framing the concumption behavior highlights the multifaceted nature of consumtion as a phenonmnon. Also, it indicates that a comprehensive understanding of these dynamics is essential for enterprises seeking to modify their strategies within an increasingly volatile market (Horner & Swarbrooke, 2020) .

Accordingly, consumption is shaped by a multitude of factors, encompassing both productive and financial elements, as well as socio-environmental considerations: a fact that is intensively addressed by consumer theory. This last one elucidates the process of decision-making within the domain of possibilities, oscillating between the evaluation of resources and the consideration of preferences. Consumption provides a sense of well-being and happiness, but only up to a certain threshold. Once this threshold is exceeded, the experience of subjective well-being is no longer sustained, particularly during periods of economic instability (Moati, 2009) that would affect and The latter, whether economic or otherwise, has the potential to disrupt the market for goods and services by either influencing prices or altering inventory levels., either by influencing prices or modifying inventory levels. This situation forces consumers to either consume excessively or insufficiently. In accordance with the concept of the “sleeping giant”, consumers, in the absence of crises, tend to disregard physical risks but they become alert at the slightest indication of danger, devoid of any opportunity for rationalisation by corporations or public entities (Grunert, 2005).

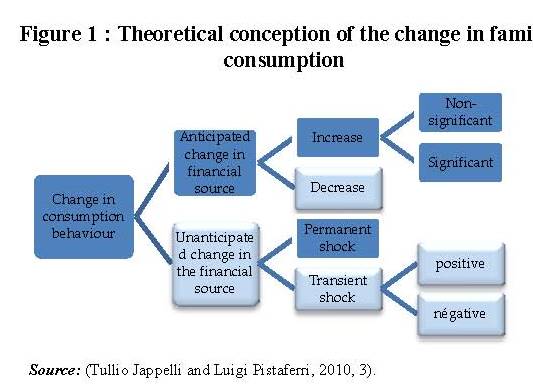

Figure 1 provides a visual representation of a synthesis of several empirical studies that seek to elucidate the relationships between changes in consumer behaviour and a range of socio-economic factors. The empirical investigation focuses on the correlation between income levels and consumption patterns. The examination and the understanding of this correlation is highly significant for the implication of economic policies and for the understanding the methodologies employed by households in devising their consumption strategies (Lardic & Mignon, 2003) . Nevertheless, it is evident that these two variables do not progress in a synchronous manner. In the short term, consumers tend to maintain their expenditure levels in the face of fluctuations in income.

It is noteworthy to mention that in the context of a crisis, the consequences of unforeseen financial shocks require a distinction between transitory shocks that are expected to have a limited impact on consumption, and permanent shocks, which are anticipated to precipitate significant changes in consumption patterns. If we assume that the impact of the pandemic is a temporary external shock, the resulting changes in consumption patterns may include both anticipated and unanticipated shifts in financial sources. The gravity of a pandemic compels consumers to engage in more deliberative decision-making regarding their financial resources (Li & al., 2020) .

Figure 1 : Theoretical conception of the change in family consumption

Source:(Tullio Jappelli and Luigi Pistaferri, 2010, 3).

Talking about Food consumption

It is largely argued that The pandemic affected every aspect of human life, including the consumer aggregate, but the impact was different across the world (Andrabi & al., 2024; Chikhi, 2021; Gu & al., 2021; Kumar & Abdin, 2021). Transformations in food production and distribution systems caused by pandemic situation have resulted in alterations to global dietary patterns. It is evident that changes have occurred in food consumption patterns both prior to and during the course of the ongoing pandemic. The food consumption has been examined through the lens of social disparities concerning gender, income, and overall well-being (standard of living) (Abdelkhair & al., 2024; Merah & al., 2021). Additionally, it is examined through a structural-functional and materialist anthropological approach, which emphasises, in addition to the classificatory examination of food systems, the prevalence of industrial processing paradigms at the expense of artisanal methodologies (Moubarac & al., 2014) .

Talking about leisure and cultural consumption

When addressing the issue of cultural consumption, it is essential to adopt a cautious approach. This may be achieved either through the application of a theoretical framework that posits a range of definitions of cultural consumption, or through an empirical lens based on data that has been gathered in a systematic manner. This consumption is influenced by a number of factors, including temporal and generational considerations, as well as the prevailing offerings and the cultural capital that facilitates the assimilation of behavioural norms related to cultural practices and their corresponding artefacts. The classification of consumption expenditures is delineated across seven primary domains, one of which encompasses leisure and culture, which further comprises subcategories utilized in household budgetary assessments or time budget surveys (Benhamou, 2008). These subcategories include expenditures on entertainment, cultural events, and media consumption, each of which reflects the diverse ways in which individuals engage with and derive meaning from cultural experiences.

Data source

The data used in this study were collected from a quantitative study that we conducted based on an online questionnaire, during the period July-September 2020. The choice of an online survey is justified by the impossibility of conducting a field survey directly among the population due to the prevailing health conditions. Nevertheless, this methodological approach to research allowed us to collect substantial data while respecting social distancing protocols, thus ensuring the safety of the participants and the integrity of the results.

Serves to mitigate health risks while simultaneously facilitating a more expansive reach, thereby enabling researchers to gather insights from a broader range of demographic groups that may have otherwise been difficult to access.

The questionnaire was constructed using Google Forms, comprising six sections and 68 questions. The sample was non-probabilistic and comprised a panel of voluntary respondents. The questionnaire was distributed randomly through a variety of channels, including mailings and social networks. The questionnaire was disseminated by our team members through a variety of channels, including private and professional networks, as well as social media platforms, over a period of several months, from July to September 2020. Following the retrieval and subsequent cleansing of the online database, a total of 1,000 responses were obtained, with 995 replies being recorded subsequent to the meticulous revision and cleansing of the database. These findings emphasise the significance of data integrity and the efficacy of our outreach strategies, ultimately informing our future decision-making processes.

A statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS software. The results obtained permitted an examination of the trends and behaviours exhibited by the participants, thereby providing invaluable insights for the formulation of future initiatives. In regard to data processing techniques, two methods were employed.

The initial approach entails the processing of the database through a descriptive statistical analysis, which is then followed by a socio-economic analysis in accordance with the conceptual framework.

The second method employs data mining techniques, with a particular emphasis on the association rule mining technique. A procedure is employed to identify patterns, correlations, or associations that occur with high frequency within a database. This approach was employed with the objective of defining the food basket of the population under study.

Focus on scholar's category

The study focused on the scholar category, which is heterogeneous in terms of demographic characteristics. This category is subject to bias due to the nature of the survey, which was conducted randomly online. It is important to recall the elements that explain why this category is the most important. These include access to technical elements (digital equipment, internet connection, etc.) and the skills necessary to complete this type of questionnaire. Additionally, it is important to consider the potential for a networking effect, given that the members of the research team who distributed the questionnaire are situated within an academic and predominantly university network.

The characteristics of the scholar category, as observed in our study, indicate that 51.4% of respondents are male and 48.6% are female, with an average age of 34.8 years. The mean family size is approximately five individuals, which is in alignment with the national average family size of Algerian households (5.9 in 2008). With regard to marital status, it is evident that there are two distinct categories: married and single. The respective response rates for these categories are 51.4% and 45.7%. In contrast, the divorced and widowed represent a relatively minor proportion of respondents. A total of 27.4% of respondents identified as heads of families. The distribution of respondents according to their professional situation reveals that the majority (60.4%) are employed, with the majority of these employed in the public sector. The remaining categories are under-represented, with student, professional training and unemployed respondents accounting for less than 20% of the total.

Results and discussion

Price variation during the containment

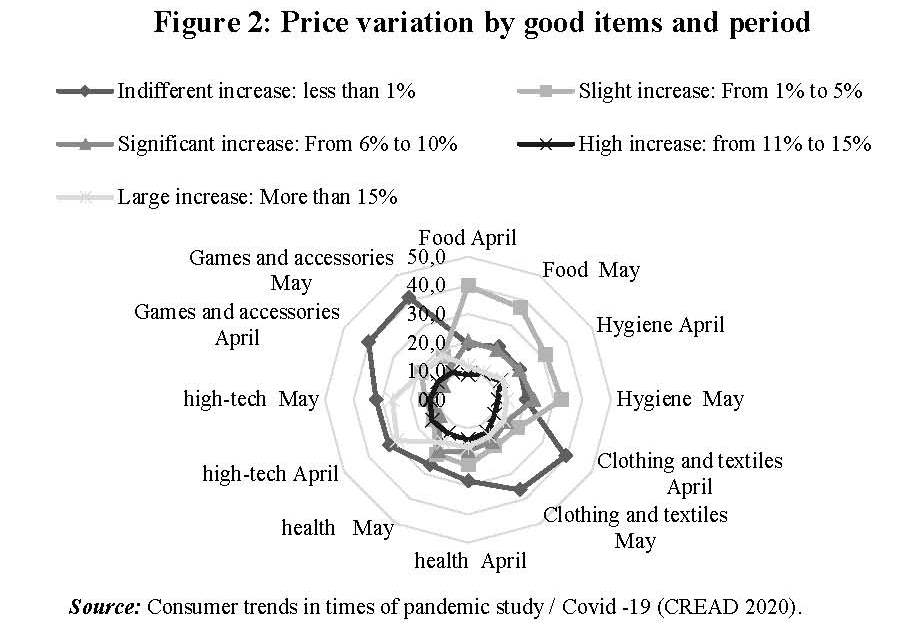

In the present study, we employ a subjective approach that is based on the perspectives of the participants. As evidenced by the findings represented in the figure 2, over 80% of participants reported a discernible increase in prices of food, hygiene, cloth, hugh tech, game during the period of containment. The findings indicate that the price augmentation is minimal due to the brief duration of the pandemic impact. Conversely, the upward trends evident in health-related expenditure and hygiene commodities indicate that, during these two periods, there was a shift in consumption patterns rather than an actual inflation in prices.

This shift in consumer behaviour indicates a prioritisation of essential goods, reflecting a broader trend whereby individuals are increasingly focusing their spending on health and safety-related products and services, rather than on non-essential items. This reorientation of consumer preferences may have long-term implications for market dynamics, potentially leading to sustained changes in supply chains and consumer preferences as individuals continue to value health-centric products.

Figure 2: Price variation by good items and period

Source:Consumer trends in times of pandemic study / Covid -19 (CREAD 2020).

How about income inequality?

Furceri's analysis of past pandemics reveals that income inequality has typically risen steadily in the five years following each health crisis. This effect was even more significant when the crisis caused an economic downturn, as seen with the current Covid-19 pandemic (Furceri & al., 2022). It is also premature to discern the full impact of a pandemic on the equality of opportunity and social mobility five years after its occurrence. The limited social mobility observed in many countries following a pandemic, particularly in terms of education and income, has the effect of slowing down the progress of a society. This is because it perpetuates existing inequalities, which in turn weakens economic growth and social cohesion (furceri & al., 2021). It is probable that our work underestimates the potential long-term consequences of the effects of the current pandemic, given the significantly greater impact on income.

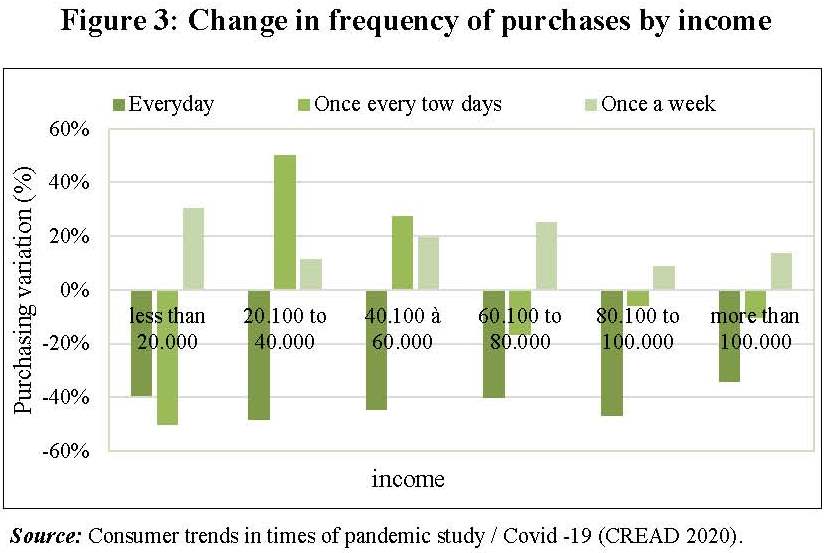

The initial findings indicate that the pandemic has highly affected the most economically disadvantaged socia strata, widening existing inequalities. Recent reports of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund has maintained that extreme global poverty and resource inequalities in emerging and low-income economies are likely to increase in 2020 (World Bank group, 2021). As illustrated in Figure 3, the data reveals that the frequency of respondents' acquisitions throughout the pandemic varies according to income levels. A transformation in the frequency of purchase was observed in a projection between the pre- and post-quarantine periods. A change in the frequency of purchase was observed, with an increase in the frequency of purchase per week for all social classes. The lower middle class appeared to be more affected by the effects of the pandemic, with a 48% reduction in daily purchases. The upper-income class (80,100 and 100,000) exhibited the second-greatest negative impact on purchase frequencies.

Figure 3: Change in frequency of purchases by income

Source:Consumer trends in times of pandemic study / Covid -19 (CREAD 2020).

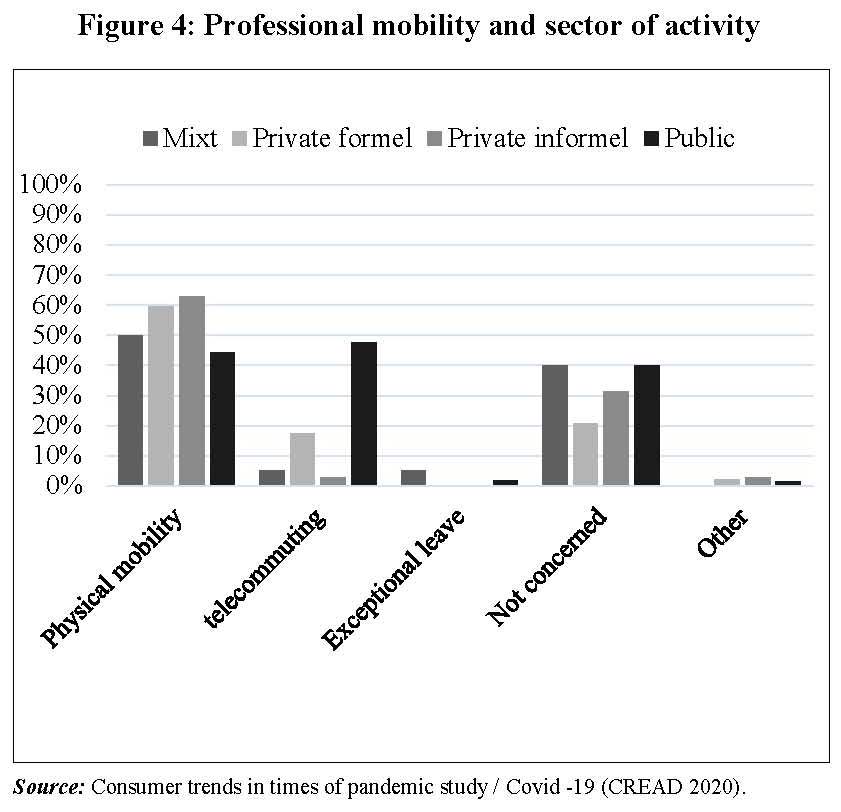

Figure 4, which illustrates the patterns of mobility in relation to employment circumstances, indicates that a substantial proportion of public sector workers engaged in remote work or on exceptional leave exhibit reluctance towards transitioning into the private or informal employment sectors. This reluctance may be attributed to concerns about job security, benefits, and the overall stability that public sector positions typically offer, underscoring the importance of understanding these dynamics in workforce planning. The initial data from developing countries indicates that the impact of the pandemic on the labour market is highly uneven, varying considerably according to the characteristics of employment, workers and companies. Otherwise, data from high-frequency surveys on the impact of the pandemic suggest that in developed countries, individuals with higher levels of education are less likely to lose their jobs than those with lower levels of education (Apedo-Amah & al., 2020).

Figure 4: Professional mobility and sector of activity

Source:Consumer trends in times of pandemic study / Covid -19 (CREAD 2020).

It is assumed that the rate of employment termination is significantly elevated within the private sector, particularly in the informal economy, due to the nature of the activities involved, which are frequently less amenable to telecommuting (Figure 4). These roles are typified by a high level of social interaction, which presents a significant challenge to the implementation of social distancing measures and increases the risk of viral exposure. Moreover, the absence of job security in these roles serves to compound the issue, as workers frequently encounter immediate financial instability when their employment is disrupted.

This precariousness has ramifications that extend beyond the individual, affecting not only livelihoods but also broader economic challenges.

A reduction in consumer spending can precipitate a cycle of decline in local economies.

Furthermore, while reduced consumer spending is a valid concern, informal economy workers often engage in local trade and barter systems that can sustain economic activity even during challenging times (Ramasimu & al., 2023). This dynamic can assist local economies in maintaining their vibrancy despite the presence of broader economic challenges. Finally, the lack of formal health benefits may appear to be a significant disadvantage. However, many informal workers rely on community health resources or alternative care systems that are more accessible and tailored to their needs (Naicker & al., 2021). It is therefore imperative to move beyond a narrow perspective that views the informal economy as a mere source of vulnerability. Instead, it is crucial to recognise its capacity for resilience and adaptability in the face of adversity. Furthermore, these networks often facilitate the formation of strong social ties, which can provide emotional support and enhance collective bargaining power among workers.

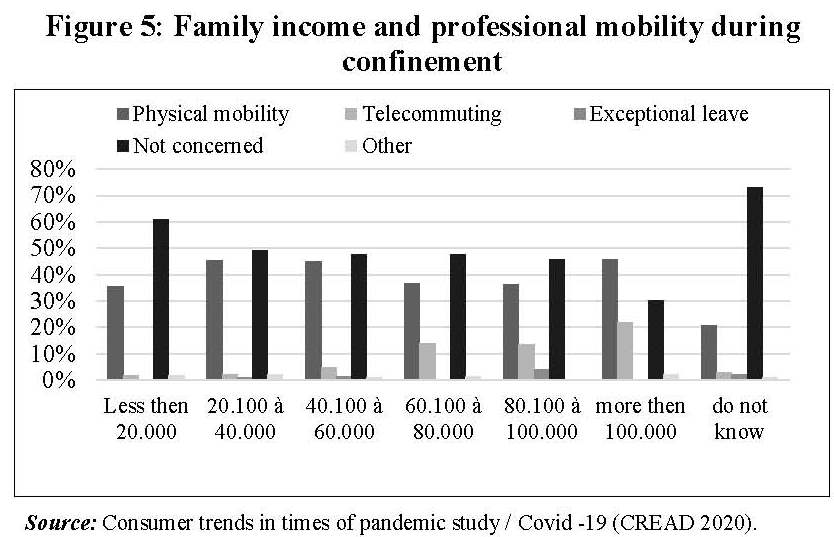

Figure 5 illustrates the distribution of respondents according to their mobility type and income level. It can be observed that individuals in lower-income brackets engage in physical mobility, whereas respondents in higher-income brackets are predominantly involved in telecommuting or are on exceptional leave.

Furthermore, it is evident that not all roles are equally suited to remote working. A significant proportion of individuals, frequently those belonging to the most disadvantaged socio-professional categories, are unable to telework (Figure 5). Even when their occupations are not deemed essential, the poorest individuals, who often lack savings, are compelled to continue working, thereby placing themselves at significant risk of infection. This is particularly evident in countries where social insurance systems are either non-existent or inadequate; where individuals are compelled to choose between continuing to work and risking illness or not working and facing the loss of financial resources (Apedo-Amah & al., 2020) .

Figure 5: Family income and professional mobility during confinement

Source:Consumer trends in times of pandemic study / Covid -19 (CREAD 2020).

The data currently available are preliminary in nature, and the future course of events remains uncertain. It is thus evident that these data will have to be supplemented by more in-depth field work and additional ethnographic studies in the future. Nonetheless, a recent article published by The United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER) endeavoured to quantify the immediate impact of the global pandemic on income and consumer expenditure. The findings indicate that global poverty will increase for the first time since 1990. The risk of increased inequality is heightened by the fact that the most marginalised and vulnerable populations are the most exposed to the health and economic risks associated with the virus. These populations are not only more susceptible to infection and to developing severe forms of the disease, but they will likely experience the economic repercussions of this crisis to a greater extent.

Firstly, those with the lowest socioeconomic status are more likely to be exposed to the disease because they often have less access to the healthcare system (Deaton, 2021). As a result, these populations are less likely to be identified and treated once they have contracted the disease. This is particularly true in countries where access to healthcare is not universal. universal (not all people can access it), and can represent a significant financial burden. In many low-income countries, particularly those that are economically disadvantaged, health systems often face significant challenges, including poor governance, corruption, inadequate infrastructure, insufficient medical equipment, a shortage of trained healthcare personnel, and mismanagement of public resources. Discriminatory practices and misuse of authority further exacerbate these issues.

In such contexts, a substantial portion of the population lacks access to essential health services, a situation that tends to worsen during pandemics, thereby reinforcing and deepening existing social inequalities. This fragile health infrastructure and unequal access to care can contribute to a rise in inequality in developing countries during and after epidemics.

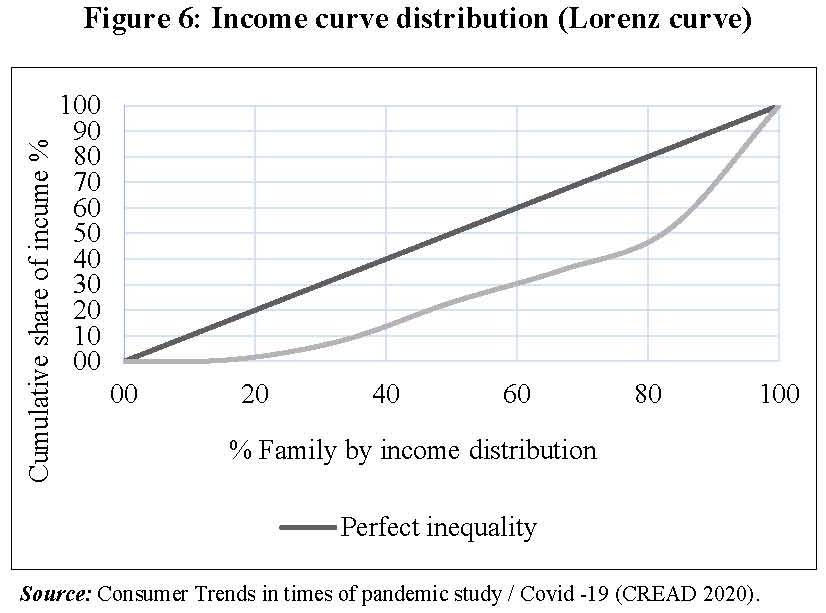

Figure 6 highlights that during the pandemic, global inequality-measured as income disparity across the population sample-continued to decline compared to 2011 (World Bank Group, 2020). The Gini index, which reflects income distribution, suggests a moderate level of inequality at 0.319.

Figure 6: Income curve distribution (Lorenz curve)

Source:Consumer Trends in times of pandemic study / Covid -19 (CREAD 2020).

Consumption behaviour

Spending and purchasing behaviour during the pandemic a safety need above all

The most recent Algerian National Household Expenditure and Living Standard Survey (ONS, 2011) indicates that the primary areas of expenditure for Algerian households are food, housing, and transportation. While, health and hygiene expenditures accounted for only 4.8% of the budget in 2011, representing a decline of 1.4 points from the figures reported in 2000 (ONS, 2011). Nevertheless, the results of our survey demonstrate a significant discrepancy between the expenditure on health and hygiene and that on food in comparison to the data from the 2000 and 2011 surveys. Although the three surveys (2000, 2011, and 2020) are not directly comparable due to differences in methodology, the 2020 survey revealed significant shifts in family consumption patterns. The largest expenditure category is consistently food, followed by hygiene and health (Table 1).

Table 1 : Evolution of the most important expenditure items in the family budget

|

Consumer Spending |

Budget coefficients 2000* |

Budget coefficients 2011* |

Significant spending 2020** |

April |

May |

Difference |

|

Food expenditure |

44,60% |

44,10% |

Food expenditure |

92,30% |

91,60% |

-0,7 |

|

Housing expenditure |

13,50% |

20,40% |

Hygiene expenditure |

55% |

55,10% |

0,1 |

|

Transport Communication expenditure |

9,40% |

12% |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Health and hygiene expenditure |

6.2% |

4,80% |

Heath expenditure |

44,90% |

45,40% |

0,5 |

Source:* consumer expenditure and standard of living survey 2011.

**Consumer trends in times of pandemic study / Covid-19 (CREAD 2020).

The discrepancy between April and May illustrates a hierarchy of preferences among these three budget items. While food expenditure retains its dominant position, it exhibits a 0.7-point decline between the two months, whereas hygiene spending demonstrates a 0.1-point increase. Health spending, on the other hand, exhibits a notable 0.5-point increase between April and May (Table 1). This illustration demonstrates a behavioural adaptation to the health crisis among families, namely a reduction in food expenditure in favour of health spending. At the outset of the pandemic, families, anticipating a potential shortage of food stocks, began to calculate their spending more carefully. This included the purchase of items such as surgical masks, dietary supplements, and medicines, as well as medical analyses related to the novel coronavirus.

Purchasing modes

The analysis of purchasing patterns represents a fundamental aspect of the investigation of consumer behaviour. The present study reveals that 95.7% of shopping during the period of confinement was conducted through direct trade. This encompasses local trade (convenience stores), which does not necessitate an increase in mobility in terms of distance and time, and which reduces exposure to the poor health conditions caused by the novel coronavirus. The remaining 25.2% of purchases were made online. Online purchasing is typically a phenomenon confined to urban areas and it has been remarkably accelerated and intensified during the pandemic. Indeed, this type of purchasing allows for minimal exposure to the virus, as payment is made online. Moreover, home delivery was emerged as a purchasing mode. When we asked respondents about the method of payment used for online shopping, a total of 90.5% of them indicated that they pay for their purchases upon delivery. Meanwhile, the remaining respondents stated that they utilised credit or debit cards (12.8%) or Visa cards (9.8%) as a means of payment. This illustrates the relatively minor role that e-payment plays in the context of trade.

Figure 7: Reasons for not buying online

Source:Consumer trends in times of pandemic study / Covid -19 (CREAD 2020).

The following figure illustrates the rationale behind the reluctance to engage in online purchasing. About 30 percent of participants mentioned a lack of knowledge regarding online purchasing, or a deficiency in this cultural practice. While, 8 percent reported either lacking of online payment means or possessing an inadequate internet connection. The majority of respondents did not embrace online purchasing due to various factors inlcunding lack of control, lack of competence, lack of confidence. This is due to a number of reasons, one of which is infrastructural in nature, namely the lack of access to an Internet connection (Merah & al., 2021). The other reason is the lack of mastery by users of the mechanics of online purchasing. This can be attributed to the limited dissemination of e-commerce culture in Algeria, which remains a relatively uncommon practice. This is due to the lack of advancement in digital payment systems and the accompanying security protocols.

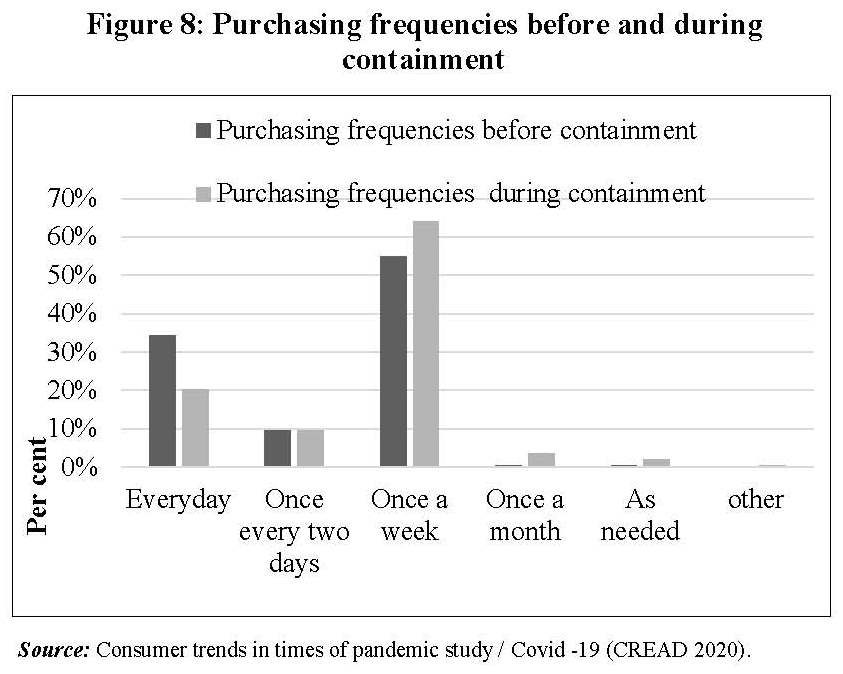

Purchase frequencies

The most common purchasing behaviour during the pandemic was purchasing once a week, followed by purchasing once every two days and then once a day (Figure 8). The variation between the two points in time (before and during the pandemic) revealed a significant change in the purchasing behaviour of scholars’ families. There was a notable increase in the frequency of purchases, with the percentage change for “once a month” purchases reaching 520%, and for “purchasing as needed” reaching 375%. Additionally, there was a decrease in the frequency of purchases for the “once a week” modality. However, there was a notable decline in the frequency of everyday purchases, with a variation rate of -40.7%.

Figure 8: Purchasing frequencies before and during containment

Source:Consumer trends in times of pandemic study / Covid -19 (CREAD 2020).

In the context of the ongoing global pandemic, the only viable solution was the implementation of social distancing measures to limit the spread of the virus. The respondent's decision to reduce their outings was also influenced by a sense of caution. Additionally, the family of scholars did not feel a pressing need to make purchases since they had been supplied with the necessary resources at the onset of the pandemic. A change in purchasing frequency was observed, with a shift from daily purchases to other frequencies, including once a month or purchases as needed. It is notable that consumer behaviour does not change rapidly. However, it has been observed that individuals do adapt to certain situations, although this is not a universal phenomenon and not a constant (Giraud-Héraud & al., 2014) .

How did families supply in the pandemic?

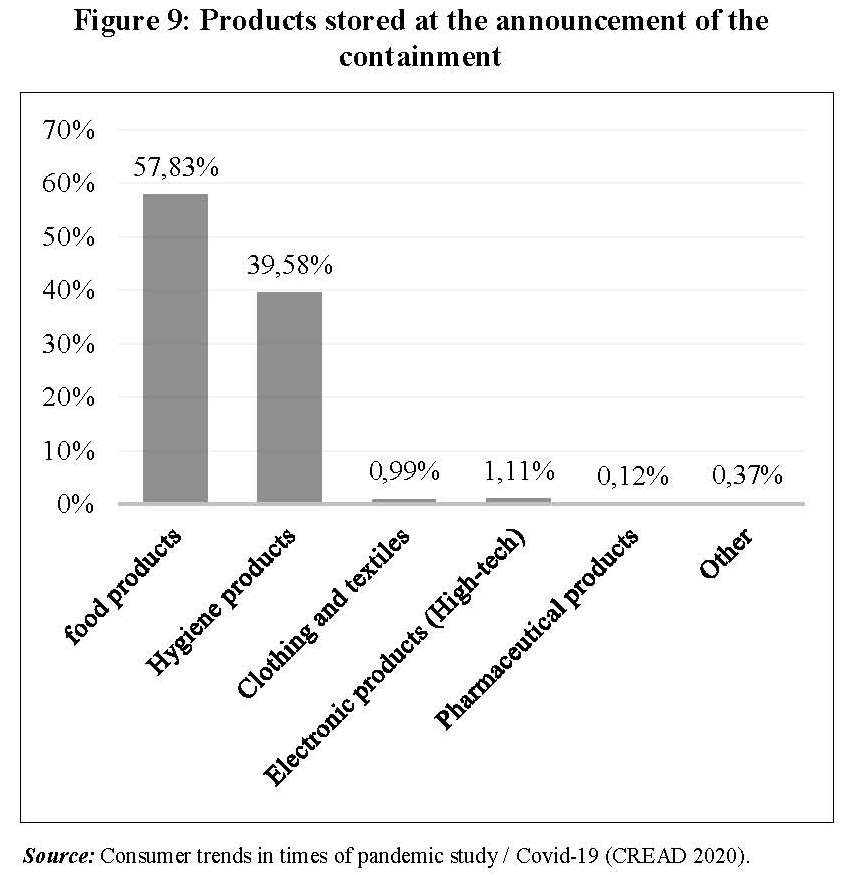

A significant proportion of respondents (40%) made substantial purchases in response to the announcement of the containment measures. This was driven by a desire to stockpile food in anticipation of potential shortages or price fluctuations.

Figure 9: Products stored at the announcement of the containment

Source:Consumer trends in times of pandemic study / Covid-19 (CREAD 2020).

Following the provision of essential supplies, families are replenished with a 57.8% stock of food items and a 40% stock of hygiene products (Figure 9). The consumer can be described as a “sleeping giant”. In the absence of a crisis, they do not consider the riskof crisis. But when the crisis occur, they would wake up at the slightest suspicion, without any possibility of rationalisation (Grunert, 2005).

Elements about food consumption

Defining food basket

The Algerian food basket has undergone a notable shift in its long-term combination, particularly with regard to the quantity of sugar consumed and the introduction of industrialised products. Additionally, there was an observed increase in the consumption of animal proteins, resulting in a notable rise in the average daily intake of animal protein among Algerians from 7.8 grams per day in 1963 to 24.1 grams per day in 2011.

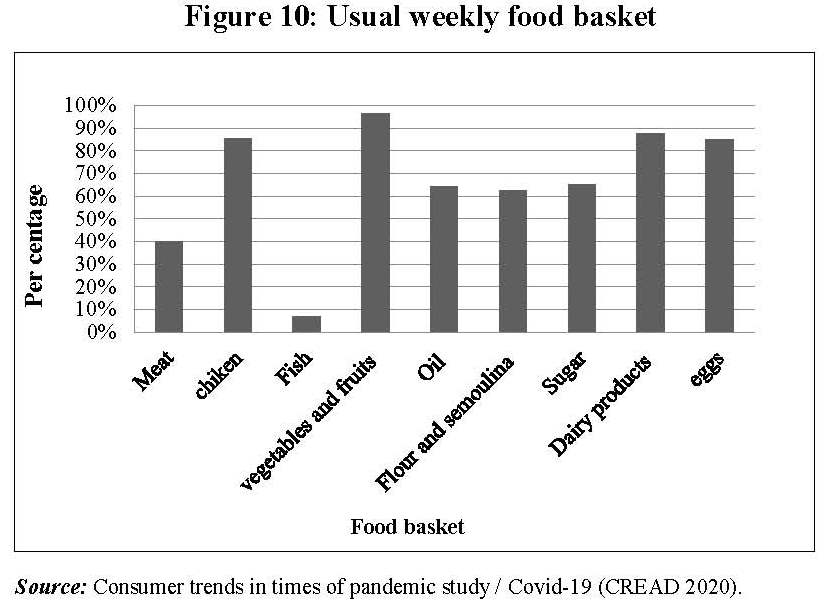

Indeed, the results of our study reveal a new trend: cereals have been supplanted from their position by vegetables and fruits, and dairy products, followed by eggs and chicken, as the main source of protein. Sugar and oil, which are still widely consumed, also feature prominently. Consequently, meat and fish are the least frequent products in the Algerians’ basket (Figure 10).

It has been observed that, particularly during the initial stages of the containment period, there was a notable enthusiasm among Algerians for the purchase and storage of flour and semolina (with all types of food storage accounting for a response rate of 57.8%). This remarkable consumption trend is not only justified by the ability of low-budget consumers to afford the costs of those products, but also because they are suitable for long-term conservation and storage.

Furthermore, during the early stages of the containment period, there was a noticeable surge in enthusiasm among Algerians for purchasing and stockpiling flour and semolina, with food storage reported by 57.8% of respondents. While exact figures are not yet available, the quantities bought were substantial. This trend can be attributed not only to the affordability of these products, making them accessible to low-income consumers, but also to their suitability for storage and long-term preservation. This observation can be analyzed from two perspectives. The results mentioned above raise several questions. Some studies have asserted that the Algerian diet has traditionally been based on cereals (E.B. & al., 1986; Letourneux & Hanoteau, 1872; Hanoteau & Letourneux, 1893; E.B., G. Camps & al., 1986). Others, however, have indicated a significant increase in cereal consumption in recent years (ONS, 2015; Chikhi & Padilla, 2014).

That said, a potential shift towards higher consumption of fruits and vegetables during the containment period may be attributable to growing awareness of health and well-being (Moati, 2009, p. 4). It could also be argued that the study may have underestimated the consumption of such foods. The food basket list used in the analysis (see Appendix 1) includes only basic cereals like flour and semolina, omitting other varieties commonly consumed by Algerians. Additionally, the frequency measure (weekly) shown in Figure 10 may have contributed to this underestimation, as these products are often purchased on a monthly basis.

Figure 10: Usual weekly food basket

Source: Consumer trends in times of pandemic study / Covid-19 (CREAD 2020).

Furthermore, the quantity of products purchased is contingent upon income category, with prices on the market serving as a determining factor. Given the price of fruit, its consumption is likely to be more prevalent among higher wage earners. However, it is not possible to determine the income threshold at which consumption of fruit decreases significantly, as it forms a single product with vegetables. The basket for the category of incomes below 20,000 DA is composed at the same level with the same recurrences in the third place in the 100,000 DA basket. However, while fish is always in the last position, its consumption increases from one level of income to another, reaching the highest proportion in the 100,000 DA and over category. Despite the improvement in protein intake, the consumption of animal protein remains an indicator of wealth. Vegetables and fruit, cereals and sugar. In the second position are oil and dairy products, while eggs are in the third position, followed by chicken in the fourth position, and so forth. As we move to the 20,000 to 40,000 DA category, the food basket undergoes a shift in priorities, with a greater emphasis placed on the purchase of dairy products and eggs, followed by chicken, cereals, and sugar and oil, which are less prevalent.

In the next category (40,000 to 60,000 DA), chicken is added to the list, while dairy products assume the second position. It can be observed that the consumption of meat, regardless of its type, becomes more prevalent at this income level. In the 60,000-80,000 category, the basket appears to be largely similar, with the exception of chicken and eggs, which occupy a more prominent position within the 80,000-100,000 DA category. In terms of meat consumption, this income category is ranked relatively high, at third place in the 100,000 DA basket. However, fish consumption remains consistently low across all income levels, even as its proportion increases with higher income brackets, reaching its highest level in the 100,000 DA and above category. It is notable that despite an improvement in protein intake, the consumption of animal protein remains an indicator of wealth.

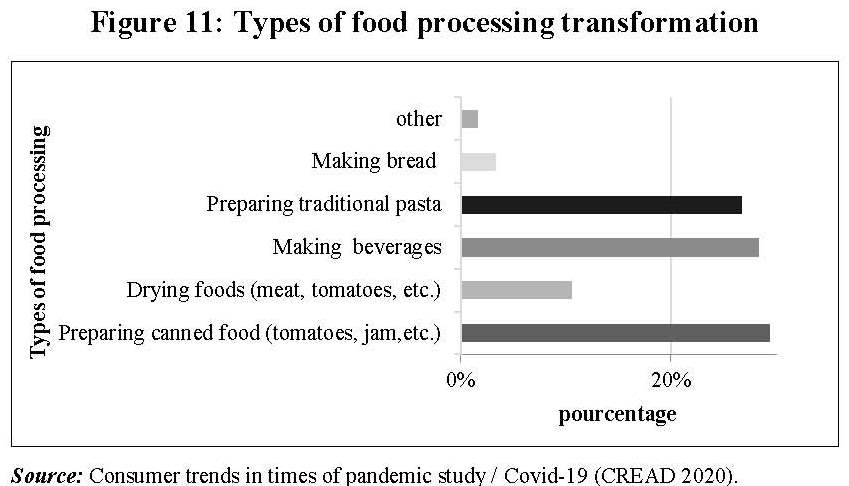

Frequency and food transformation logic

A change in the frequency of food transformation was observed in a projection between the periods preceding, during and following the period of confinement. The data indicates a tendency towards alterations in consumption patterns that have been influenced by the health crisis, which are likely to persist or even intensify during the post-Covid era. A survey of family dietary habits (Oussedik et al., 2014) revealed a preference for traditional bread (galette) over industrialised bread. Therefore, it can be inferred that the quantity of semolina and flour purchased during the period of containment was likely utilised, among other purposes, for the preparation of traditional bread, which the Algerians differentiate from what is commonly referred to as “baker's bread”. Consequently, the preparation of traditional pasta may also encompass the production of traditional bread, despite the observation of a declining trend in domestic grain transformation (Oussedik & al., 2014).

Figure 11: Types of food processing transformation

Source: Consumer trends in times of pandemic study / Covid-19 (CREAD 2020).

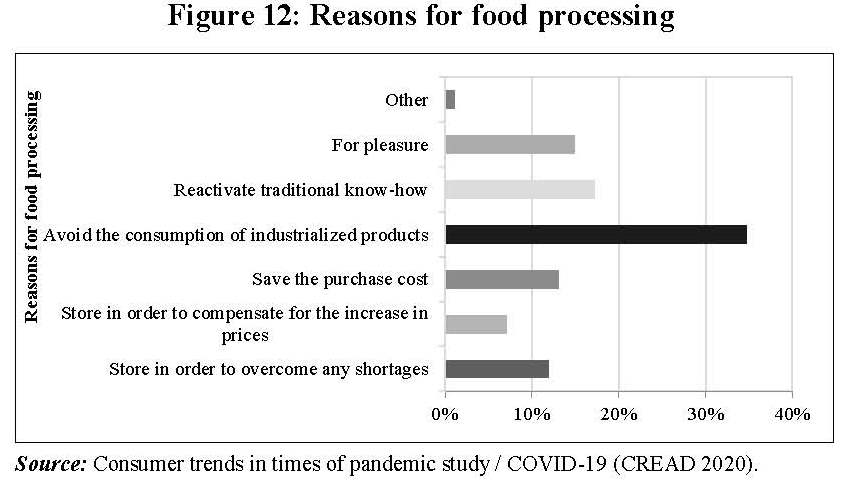

The field of food processing also encompasses the preparation and preservation of products that are not commercially available, such as dried meat. The process of drying and preserving, along with all the associated culinary and gustatory memories, is currently confined to a limited number of families (Oussedik & al., 2014). A significant proportion of respondents (34.7%) engage in food processing as a means of circumventing the purchase of industrialised products, citing health concerns as a primary motivation. This new relationship with oneself emphasises the concept of well-being, while also facilitating the reactivation of traditional skills and a reduction in purchasing costs (Figure 11).

Figure 12: Reasons for food processing

Source: Consumer trends in times of pandemic study / COVID-19 (CREAD 2020).

The results indicated that the availability of goods has a significant impact on the formation of a consumerist model, particularly given that the price increase for industrialised food products is less pronounced than that of fresh agricultural products (ONS, 2011).

The globalisation of food policy has resulted in the standardisation of dietary habits through the continuous development of an industrial food industry that reflects an increasingly industrialised mode of production (Malassis, 1977). This increased availability of goods paradoxically reduces the amount of time women need to spend on domestic tasks, particularly cooking. This effect is especially pronounced among housewives, as noted by Mary Douglas (Douglas, 1979).

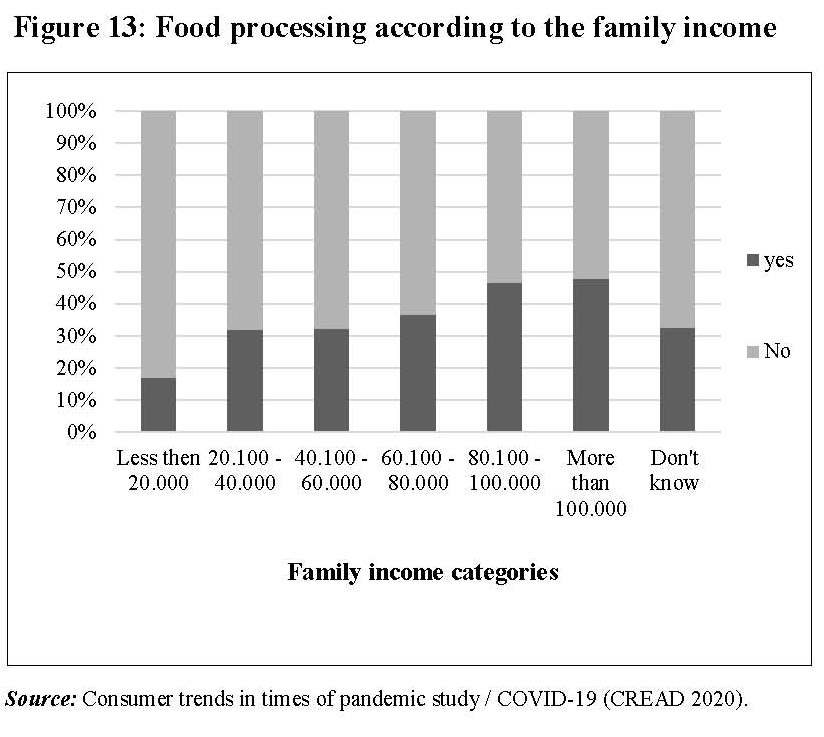

The transformation, indicative of a standard of living

With domestic food processing proportional to family income. Indeed, the rate of respondents declaring that they process food increases as their income rises, reaching 48.9% in the categories earning over 100,000 dinars. (Please refer to Figure 13).

Figure 13: Food processing according to the family income

Source: Consumer trends in times of pandemic study / COVID-19 (CREAD 2020).

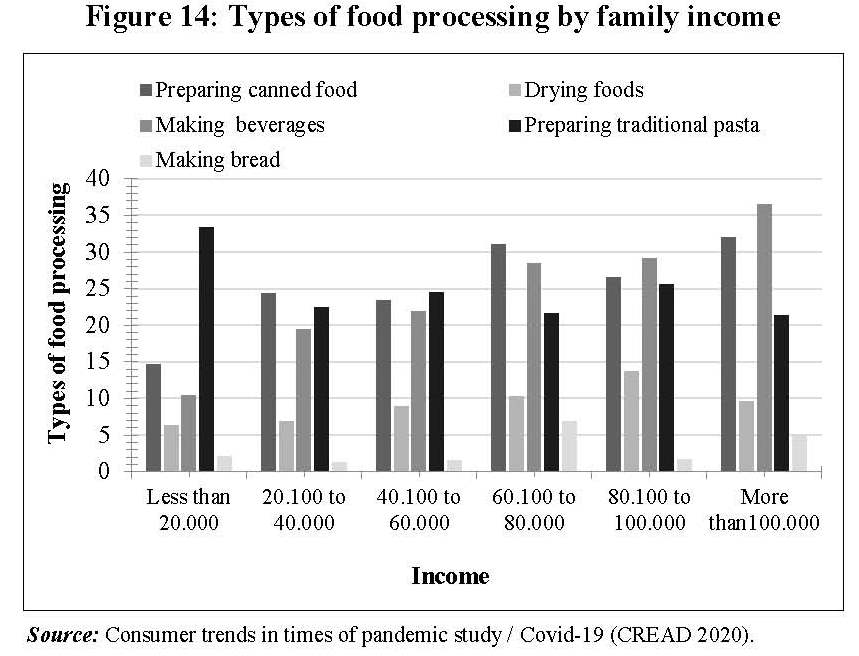

Figure 14: Types of food processing by family income

Source: Consumer trends in times of pandemic study / Covid-19 (CREAD 2020).

The most common forms of food processing among the families surveyed were the preparation of canned food and drinks, and traditional pasta. This indicates that this mode of consumption is aligned with urban living patterns, given that the majority of the population resides in Algiers. The preparation of beverages and, to a lesser extent, the preparation of home-canned goods is particularly prevalent among the highest income groups (with an income of 80,000 DA or more).

Conversely, the preparation of traditional pasta represents the most significant form of processing undertaken by low-income families. This report indicates the basket of each income category, given that the preparation of drinks and canned goods at home requires the supply of vegetables and fruits, which are sometimes inaccessible to low-income groups. The practice of food processing is more prevalent among retirees, contingent on their professional circumstances. This outcome can be attributed to a number of factors, including a decline in income levels (Mendil & al., 2018) among this demographic, which necessitates a modification of consumption patterns to reduce expenditure. Furthermore, this practice is associated with the elderly population's concern for their overall well-being and their greater availability in terms of time, as well as their probable knowledge in this field.

Leisure consumption

Purchases for culture and entertainment

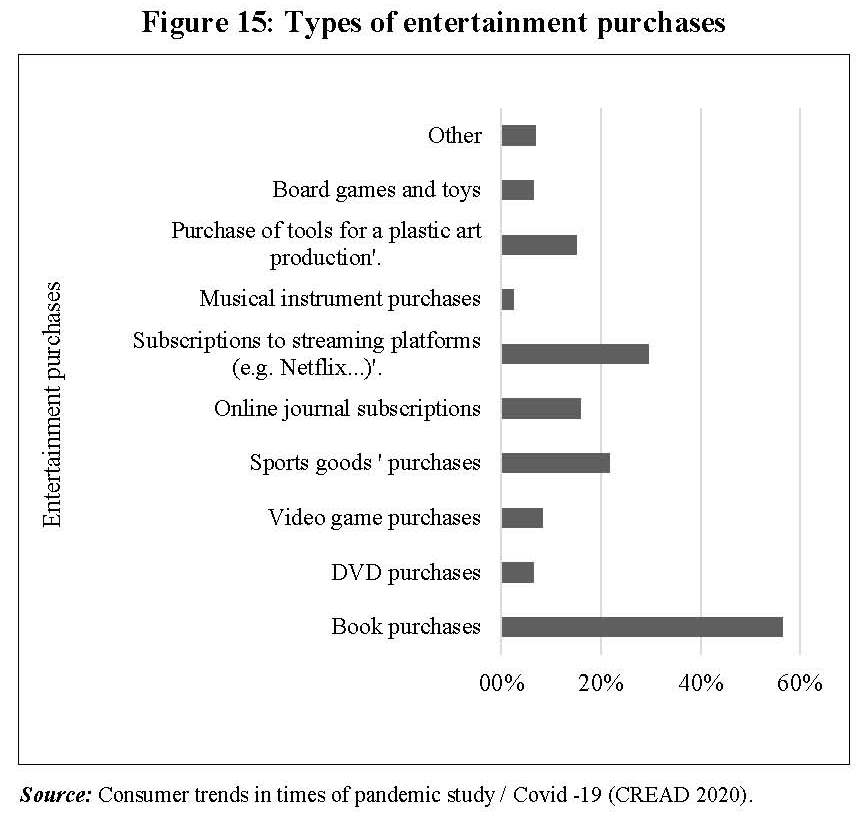

It is recommended that acquisitions pertaining to cultural and recreational activities be characterised as weak signals. A mere 27% of participants engage in such purchases, in stark contrast to expenditures on nutrition and health, which exhibit an even greater escalation during periods of crisis. It is, however, important to examine this consumption through the lens of sub-groups that elucidate consumer preferences. Such sub-groups may include factors such as age, income level and geographic location, all of which exert a significant influence on individual spending habits.

Figure 15: Types of entertainment purchases

Source: Consumer trends in times of pandemic study / Covid -19 (CREAD 2020).

In this context, respondents demonstrated a proclivity for investing in the acquisition of books, with 56.6% expenditure, as well as subscriptions to streaming platforms and the purchase of sports items (Figure 15). The three categories illustrate a diverse range of consumption patterns, encompassing active sedentary activities (books), passive sedentary activities (streaming), and active non-sedentary activities (sports articles).

This consumption pattern demonstrates the consumer's desire to occupy their time in a manner that adapted to the constraints imposed by confinement. It also illustrates a diversification of leisure and entertainment activities, which are tailored to meet the physical, psychological and intellectual needs of the consumer.

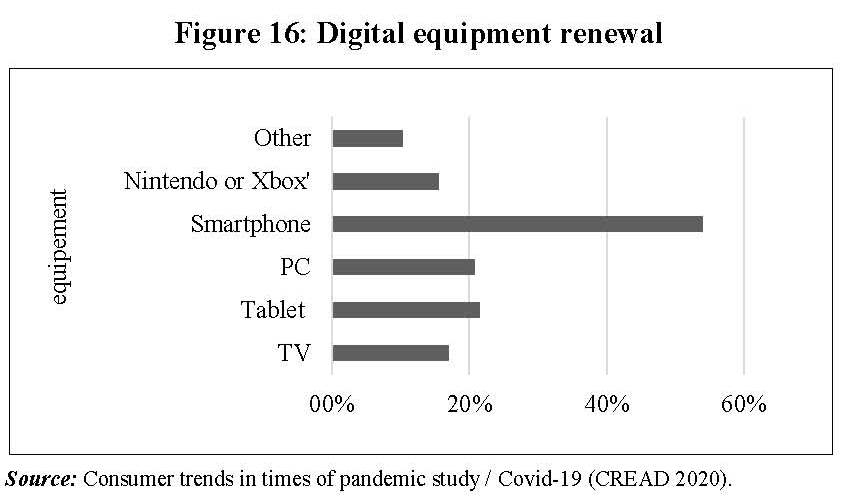

Expenditure on digital equipment

In the context of cultural consumption, investment in new media constitutes an important element. A total of 15% of respondents indicated that they had purchased or renewed digital equipment. The purchase of a smartphone is the most prevalent form of digital equipment purchased, with 54.1% of respondents indicating this as a recent acquisition. Given the multifaceted capabilities of this digital medium, it is unsurprising that respondents cited a range of reasons for purchasing it, including communication, social networking, entertainment, and other applications. This investment is followed by the purchase of tablets (21.1%) and computers (20.7 %), which can be used for a variety of intellectual and cultural activities, as well as for functional and durable purchases for all family members, or for specific uses for each member (Figure 16).

Figure 16: Digital equipment renewal

Source: Consumer trends in times of pandemic study / Covid-19 (CREAD 2020).

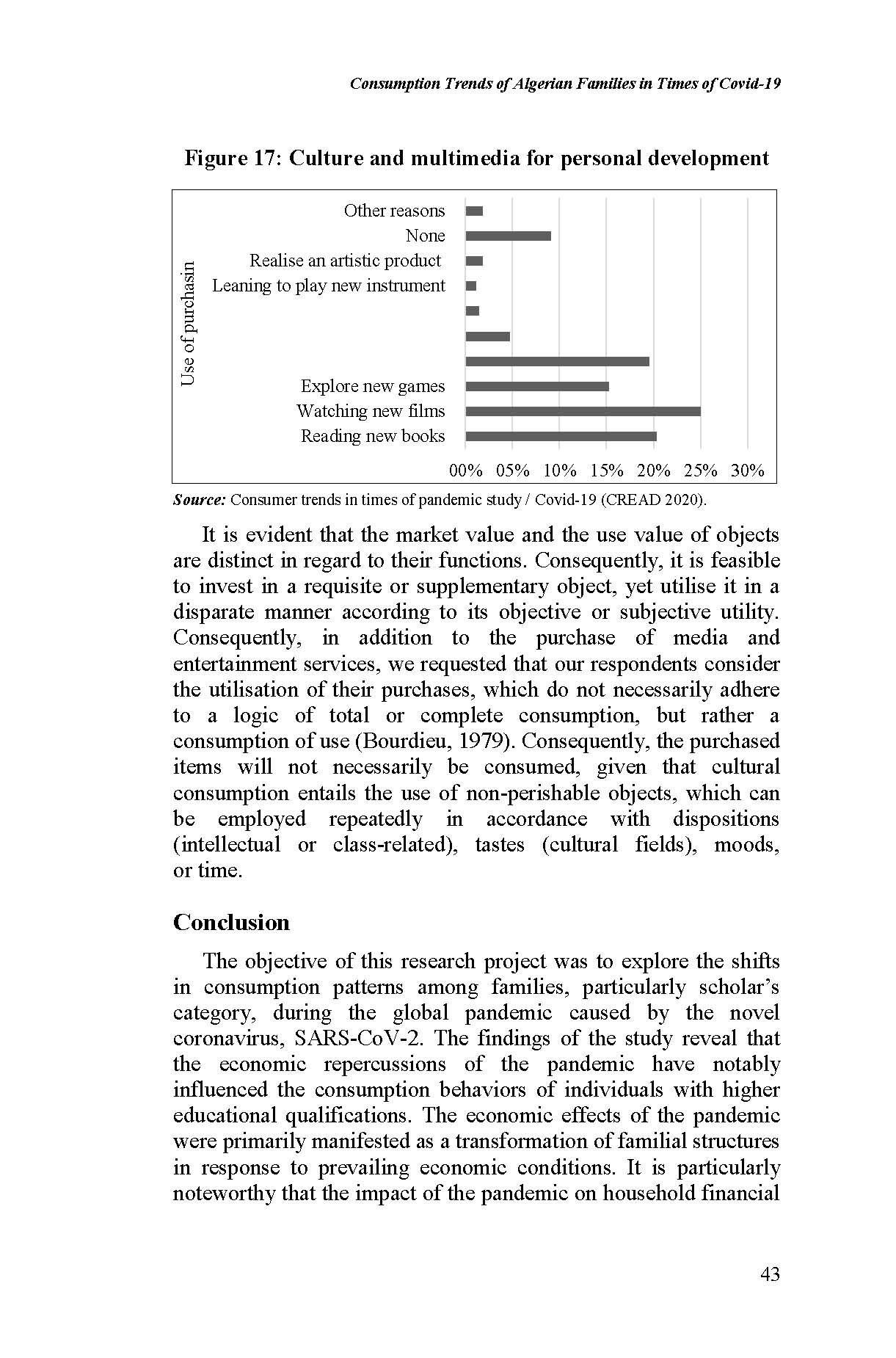

Figure 17: Culture and multimedia for personal development

Source: Consumer trends in times of pandemic study / Covid-19 (CREAD 2020).

It is evident that the market value and the use value of objects are distinct in regard to their functions. Consequently, it is feasible to invest in a requisite or supplementary object, yet utilise it in a disparate manner according to its objective or subjective utility. Consequently, in addition to the purchase of media and entertainment services, we requested that our respondents consider the utilisation of their purchases, which do not necessarily adhere to a logic of total or complete consumption, but rather a consumption of use (Bourdieu, 1979). Consequently, the purchased items will not necessarily be consumed, given that cultural consumption entails the use of non-perishable objects, which can be employed repeatedly in accordance with dispositions (intellectual or class-related), tastes (cultural fields), moods, or time.

Conclusion

The objective of this research project was to explore the shifts in consumption patterns among families, particularly scholar’s category, during the global pandemic caused by the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2. The findings of the study reveal that the economic repercussions of the pandemic have notably influenced the consumption behaviors of individuals with higher educational qualifications. The economic effects of the pandemic were primarily manifested as a transformation of familial structures in response to prevailing economic conditions. It is particularly noteworthy that the impact of the pandemic on household financial resources was more significant than the alterations in pricing mechanisms. The fluctuations in prices were largely precipitated by panic-driven behaviours, which emerged in response to the constrained availability of specific food items following the implementation of lockdown protocols.

With regard to financial resources, our study revealed a slight decrease, which can be attributed to factors such as partial unemployment and the suspension of various economic activities. In response to these challenges, families employed a range of strategies, including the usage of precautionary savings and support networks, encompassing aid from relatives, governmental initiatives, and community organisations.

As we undertake a more comprehensive investigation into the socioeconomic disparities that exist, it becomes increasingly evident that the impact of the ongoing pandemic is likely to exacerbate existing income inequalities, even within the context of the academically oriented category. It is anticipated that those belonging to lower socioeconomic groups will experience the most severe consequences, primarily due to their heightened susceptibility to both health-related and economic vulnerabilities. In this context, the extension of social security nets to safeguard at-risk populations during the pandemic has been of the utmost importance. It is equally important to transition state assistance from a mere financial support system to one that provides more substantial assistance, addressing the specific needs of those affected.

Our analysis additionally reveals a notable transformation in family consumption preferences throughout the pandemic, characterised by an intensified focus on essential commodities, particularly within the domains of food security, health, and hygiene.

In addition, this period witnessed a qualitative shift in dietary patterns, with families increasingly gravitating towards more nutritious food choices, such as fruits and vegetables, that reflect their economic status. A more balanced diet is often associated with increased wealth, whereas households with lower income levels tend to exhibit less variety and lower nutritional quality in their food options.

Furthermore, families have adapted to the “new normal” in different ways, striving to instill a sense of security through the reintroduction of traditional culinary practices and food preparation techniques. This adaptation serves not only to improve health and economic interests, but also to reestablish a connection with cultural heritage. The growth of online shopping and home delivery services has become a significant strategy for reducing exposure to the virus. Nevertheless, the imperative for a comprehensive integration of e-commerce into the economic framework, particularly through the development of secure online payment systems, cannot be overstated.

Furthermore, the pandemic has precipitated a transformation in cultural and leisure consumption patterns, as individuals sought to occupy themselves during the period of social isolation. This transition has resulted in a diversification of entertainment pursuits, with offerings tailored to satisfy various physical, psychological, and intellectual needs.

In conclusion, the interplay between economic challenges and shifting consumer preferences during this unprecedented period underscores the resilience and adaptability of families navigating a landscape transformed by the pandemic. As businesses respond to these changes, innovative solutions are emerging, redefining traditional market dynamics and ushering in a new era of digital entrepreneurship. This evolution highlights the critical role of technology in modern society while emphasizing the need for businesses to remain agile and responsive to consumer needs. Ultimately, this transformation sets the stage for a more interconnected and dynamic marketplace.

Bibliography

Abdelkhair, F. Y. F., Soharwardi, M.-A., Mazrou, Y. S. A., Mudawi, S. S. A., Ashraf, I., Ashraf, S., & Mohammad, R. A. (2024). Pandemic COVID-19 And Consumer Behavior : Moderation And Mediation Of Socioeconomic Factors. Migration Letters, 21(S5), 1569‑1581.

Andrabi, U.; Ashraf, A. & Chhibber, P. (2024). Impact of the Pandemic on Consumer Behavior, A Review. In N. Singh, P. Kansra, & S. L. Gupta (Éds.), Navigating the Digital Landscape (p. 167‑180). Emerald Publishing Limited.

Apedo-Amah, M-C.; Avdiu, B.; Cirera, X.; Cruz, M.; Davies, E.; Grover, A.; Iacovone, L.; Kilinc, U.; Medvedev, D. & Maduko, F. O. (2020). Unmasking the impact of COVID-19 on businesses : Firm level evidence from across the world. The World Bank. https://urlz.fr/tqHS

Arninda, D.; Soesilo, A.-M. & Samudro, B. (2022). Rationality and Irrationality in the Consumption Behavior of the Vespa Lovers Community in Madiun City. International Journal of Economics, Business and Management Research, 06(08), 371‑379.

Askari, M.-Y. & Refae, G. A. E. (2019). The rationality of irrational decisions : A new perspective of behavioural economics. International Journal of Economics and Business Research, 17(4), 388.

Auzan, A.-A. (2020). The economy under the pandemic and afterwards. Population and Economics, 4(2): 4-12.

Baker, S.-R., Farrokhnia, R. A., Meyer, S., Pagel, M., & Yannelis, C. (2020). How does household spending respond to an epidemic? Consumption during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. The Review of Asset Pricing Studies, 10(4), 834‑862.

Beckert, J. (2009). The social order of markets. Theory and Society, 38(3), 245‑269.

Benhamou, F. (2008). L’économie de la culture. Paris : La Découverte.

Bosserelle, E. (2017). Économie Générale : 6ème édition entièrement revue et mise à jour. Post-Print: https://urlz.fr/tqI1

Bourdieu, P. (1979). La distinction : Critique sociale du jugement (Le sens commun), Paris : Les Éditions de Minuit.

Bourdieu, P. (1993). Questions de sociologie. Paris : Les Éditions minuit.

Chikhi, K. (2021). L’impact de la crise sanitaire du Covid-19 sur le comportement de consommation des Algériens. Revue d’Études en Management et Finance d’Organisation, 6(1).

Deaton, A. (2021). COVID-19 and global income inequality. LSE Public Policy Review, 1(4).

Deaton, A., & Muellbauer, J. (1980). Economics and consumer Behavior. Cambridge University Press.

Douglas, M. (1979). Les structures du culinaire. Communications, 31(1), 145‑170.

Camps, G. & al., (1986). Alimentation. Encyclopédie berbère, (4), 472-529.

Furceri, D. , Loungani, P. , Ostry, J.-D. & Pizzuto, P. (2022). Will COVID-19 Have Long-Lasting Effects on Inequality? Evidence from Past Pandemics. The Journal of Economic Inequality, 20(4), 811‑839.

Giraud-Héraud, E. , Aguiar Fontes, M & Seabra Pinto, A. (2014). Crise sanitaires de l'alimentation et analyses comportementales. Working Papers hal-00949126, HAL.

Grunert, K.-G. (2005). Food quality and safety : Consumer perception and demand. European Review of Agricultural Economics, 32(3), 369‑391.

Gu, S., Ślusarczyk, B., Hajizada, S., Kovalyova, I. & Sakhbieva, A. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Online Consumer Purchasing Behavior. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 16(6).

Herrero, M.; Hugas, M.; Lele, U.; Wirakartakusumah, A. & Torero, M. (2023). A shift to healthy and sustainable consumption patterns. Science and innovations for food systems transformation, 59. pp 59-85.

Horner, S. & Swarbrooke, J. (2020). Consumer Behaviour in Tourism (4th edition). London: Routledge.

Irace, T., & Lojkine, U. (2020, mai 12). Économie de pandémie, économie de guerre. Le Grand Continent.

Kumar, R., & Abdin, M. S. (2021). Impact of epidemics and pandemics on consumption pattern : Evidence from Covid-19 pandemic in rural-urban India. Asian Journal of Economics and Banking, 5(1), 2‑14.

Langlois, R.-N. & Cosgel, M.-M. (1996). “The Organization of Consumption”. Working papers (07), University of Connecticut, Department of Economics.

Lardic, S. & Mignon, V. (2003). Fractional Co-integration between Consumption and Income. Economie & prévision, 158(2), 123‑142.

Letourneux, A., & Hanoteau, A. (1872). La Kabylie et les coutumes kabyles. Paris : Imprimerie Nationale.

Li, M.; Zhao, T. ; Huang, E. & Li, J. (2020). How Does a Public Health Emergency Motivate People’s Impulsive Consumption? An Empirical Study during the COVID-19 Outbreak in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(14).

Malassis, L. (1977). Économie agro-alimentaire. Économie rurale, 122(1), 68‑72.

Mendil, D., El Moudden, C., & Hammouda, N.-E. (2018). Le système de retraite algérien : Redistribution intragénérationnelle

et inégalités des pensions. Retraite et société, (2), 75‑96.

Merah, A., Boussaid, K., Merabet, I., Hadefi, A.-Z. & Djani, F. (2021). Série Impact COVID-19 : Les tendances de consommation en temps de pandémie Covid-19

Moati, P. (2009). Cette crise est aussi celle de la consommation. Les Temps Modernes, 655(4), 145‑169.

Moubarac, J.-C., Parra, D. C., Cannon, G., & Monteiro, C.-A. (2014). Food Classification Systems Based on Food Processing: Significance and Implications for Policies and Actions: A Systematic Literature Review and Assessment. Current Obesity Reports, 3(2), 256‑272.

Naicker, N., Pega, F., Rees, D., Kgalamono, S. & Singh, T. (2021). Health services use and health outcomes among informal economy workers compared with formal economy workers : A systematic review and meta-analysis. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(6), 3189.

ONS. (2011). Dépenses de consommation des ménages algériens en 2011, statistiques sociales No. 183; série S : statistique sociale, p. 62.

Oussedik, F., Boucherf, K., Lassassi, M., Merah, A., Kennouche, T., Merabet, I. & Miles, R. (2014). Mutations familiales en milieu urbain. Algérie 2012. Oran : CRASC.

Ramasimu, M. A., Ramasimu, N.-F. & Nenzhelele, T. E. (2023). Contributions and challenges of informal traders in local economic development [Special issue]. Corporate Governance and Organizational Behavior Review, 7(2), 236–244.

Simon, H.-A. (1997). Models of Bounded Rationality : Empirically grounded economic reason. MIT Press.

World Bank group. (2020). Poverty and inequality platform [Jeu de données]. https://urls.fr/X-M5V6

World Bank group. (2021). Updated estimates of the impact of COVID-19 on global poverty : Looking back at 2020 and the outlook for 2021. World Bank Blogs.

Ziar, H., Fetouch, M., Keddar, K., Belmadani, N., Amtout, L. & Riazi, A. (2022). Food behavior of the Algerian population at the time of the Covid-19 : The first survey carried out in the western Algerian region. South Asian Journal of Experimental Biology, 12(3), 385‑397.