Ammara BEKKOUCHE:University of Science and Technology of Oran Mohamed Boudiaf (USTO), 31 000, Oran, Algeria.

More than three centuries of European colonization throughout the world by Spain and Portugal will implement new and vast program…of urbanization (Benevolo, 1988, p. 307). France applied the lesson in Algeria, benefiting from the teachings of its predecessors especially where space planning1 was concerned, but it did add its versions according to the particularities of the context and the moment. Sidi Bel Abbès precisely, is an interesting case in point to study in order to decipher some of the colonial issues that have prevailed in its regional planning. Alexis de Tocqueville’s (Tocqueville, 1988) reports on the Colony in Algeria are extremely enlightening in terms of understanding the strategy behind the creation of the town. His ideas are reflected in many aspects of the colonial centers founded in Algeria during his lifetime, including Sidi Bel Abbès, which is currently presented by the Guides Bleus as a town of little interest to tourists. Some people, relying on the concept of the creation ex-nihilo2, describe it as a new town, but the expression3 is inappropriate given the circumstances which saw its birth. In fact, several factors at different levels were behind its foundation in 1842. Upstream, obviously appears the colonization of Algeria in 1830, which proceeded in stages to occupy the already existing towns and create stopover shelters over long distances before settling in permanently.

The creation of Sidi Bel Abbès was part of this network logic, which also served as an observatory to monitor the South (Bastide, 1880, p. 18-20-22) and was in line with the need to “protect and provide supplies to troops travelling from Oran or Mascara to Tlemcen” (Munoz, 1931, p. 197).

The town is remarkable for the composition of its central core, the geometry of which and the road structure are reminiscent of cultural and technical models that partly synthesize those of the French bastides of the Renaissance and the spirit of geometric (Benevolo, 1988, p. 316) regularity. It is also reminiscent of the design of the new chessboard like towns laid out by the Spaniards for the conquest of Southern Central America in the 16th century (Benevolo, 1988). The model will be propagated by the French and the English over the following centuries, and it was as such that it served the purposes of colonization, the history of which has yet to be written4. As a colonial city then, what were the processes involved in its creation and evolution, as well as the decisive urban planning principles behind the organization of its space? By examining the types of action taken on space and society, we can approach this question by comparing the historical data on the site with the data on its development.

Location Principle or the Spirit of Tocqueville in the Genesis of the City

The first thing to be noted when looking at the geographical position of Sidi Bel Abbès is its perfect centrality in the middle of a cluster of towns that are important in the structure of the north-western region of Algeria. In what way would this apparently meaningless detail, have anything to do with the colonizing principles concerning the settlement of the city? It is indeed located at equal distance from Oran, Tlemcen, Mascara and Dhaya5. The latter, which does not rank with the other cities, was created in the form of a redoubt, to the south on the mountains bordering the Tell before the high steppic plains (Reutt, 1949, p. 9). It owed its importance to its geographical position, completing the framework of the territory to be colonized on a regional scale, while at the same time marking a milestone on the road to the Sahara: “The security of Oran required the occupation of the whole country, right up to the edge of the Tell. The Mekerra plain, on the road linking Oran to the Dhaya post, could not be left empty” (Reutt, 1949, p. 34). A synchrone reading of the facts characterizing the period of colonization between 1830 and 1880 gives a better understanding of the reasons for its situation and, to a certain extent, the principles of its geographical organization. In other words, the aim was to colonize what was then known as the province of Oran.

One of the factors favorable to the situation of Sidi Bel Abbès is to be attributed to the characteristics of the Mekerra plain crossed by natural ways of communication (Reutt, 1949, p. 65).

“Indeed, if a strong occupation did not close the natural road of the Mekerra to the horsemen of the south, these plundering gangs could easily advance through a defenseless country, and through a path without obstacles, into the fertile plains of M'léta and Sig. The squares of Mascara and Tlemcen, being turned inwards, lost their action in the defense of the colonized shores and could see their communications with Oran endangered. It was therefore urgent to fill up the opening that was thus forming on this line of Mascara - Tlemcen, the length of which, one hundred and forty kilometers, was too considerable to allow effective surveillance on the part of its two points of support” (Bastide,1880, p. 24).

The role of the crossroads, at this level of the territory, is rightly appreciated as a crucial hub where existing forms of life could be neutralized and colonization extended to other regions, including Morocco. In addition to the towns, there were also, and above all, the tribes who organized the space according to the settlement patterns of the time. Those tribes began to pose problem when they became active forces around the Emir Abdel Kader, who tried his influence in an attempt to halt the colonial intrusion. In this atmosphere of war, the need to create a town would prove an ideal way of pursuing their colonial domination while the attacks continued:

“No one can tell when the war will be over. Waiting for it to end in order to colonize means postponing the fundamental issue indefinitely [...]. [...] Colonization and war must therefore go hand in hand, if at all possible” (Tocqueville, 1988, p. 94).

After the possibility of occupying Mostaganem or Arzew6 was brushed aside, this idea became clearer:

“...after having seen the place, I can declare that, in my opinion, nothing could be more absurd than wanting to colonize Mostaganem at the present time... The country surrounding Mostaganem is, to tell the truth, very fertile. But it is a five-days walk from our main settlement, Oran, and you could only cross the space between there and Oran by marching with an army; on the seaward side, the approach to Mostaganem is so dangerous that, even in the summer months, it is very rare that men and goods could be landed there safely” (Tocqueville, 1988, p. 96).

It is part of a coherent coverage of the territory according to a suitable grid for a more widely controlled, far-reaching presence in the area:

“The entire Tell is now covered by our posts, like an immense network whose very tightly knit meshes in the west become wider the further east you go. In the Tell of the province of Oran, the average distance between all the posts is twenty leagues. Consequently, there is no tribe there that couldn't be caught on the same day from all four sides at once, upon the very first move it would like to make” (Tocqueville, 1988, p. 163).

Twenty leagues, corresponding to a journey of around 80 kilometres is the approximate distance separating Sidi Bel Abbès from the surrounding towns7. This key position at the intersection of the four main roads, where communications were easy, also had the distinct advantage of an immense fertile plain (Tocqueville, 1988, p. 163) irrigated by the Oued Mekerra and several springs. A golden opportunity that justified and reinforced the choice of a site with such lucrative potentialities that it weighed in on our decision to drain the marshes that characterized it. The plain had this particular characteristic of being subject to flooding at a rate that is currently causing ecological problems for the town, with far-reaching economic consequences.

The Principles of Mobility and the Economic Weapon

At the outbreak of the colonial invasion, the “Belabbessian” territory was part of a form of spatial and social organization structured into tribes scattered throughout the region. For its colonization, it gave rise to types of intervention on the relationships of this logic, in which Machiavelli's advice on acquiring principalities (Machiavel, 1998) is recognized. The link is to be made when, in the course of investigations aimed at explaining occurrences, relationships emerge that fall within the scope of his courses on the ends and means to be used in relation to various situations. Among other actions, the most effective way to begin colonizing the site was to use military mobility in space and to interfere with trade. Controlling trade is a formidable weapon, as we know that one of the fundamental criteria for regional structuring is based on the market (Beaujeu-Garnier, 1980, p. 318). Tocqueville's reflections on this subject corroborate this strategy, particularly with regard to the organization of the army corps on expeditions:

“What is unbearable in the long run for an Arab tribe is not the passage, time and again, of a large army corps on its territory, but the proximity of a mobile force which at any moment and in an unforeseen manner can fall upon it”

“In the same way, we must recognize that what can truly protect our allies is not a large army that would come from afar to join them in fighting the common enemy, but the possibility of calling us to the rescue at a moment's notice if Abd-el-Kader approaches. We can therefore say that it is probably better to have several small, mobile forces constantly moving around fixed points than large armies moving at long intervals over an immense portion of land.

Wherever you can position a corps in such a way that it can be released if necessary and run across the country, you should do so. That, in my opinion, is the rule. But for the positioning or supplying of these small corps, considerable expeditions are needed time and again” (Tocqueville, 1988, p. 79).

This approach led to the creation on the ground of redoubts which could be defined as isolated, solid fortifications and places to retreat to in the event of an attack. They punctuate the land to mark its limits, like the spider weaving its web to paralyze any movement within its territory.

In line with the tactic of mobility and concerning the register of commercial activities, he added: “The most effective means of reducing tribes is to prohibit trade” (Tocqueville, 1988, p. 78). This circumstance is most appropriate in the case of Sidi Bel Abbès, where a region-wide souk used to be held on Thursdays, the traces of which can be seen in the Arab market. As to what is still visible8, its position to the north of the Mekerra, is in the nature of trade, at the crossroads of the routes coming from the surrounding towns. It must be assumed that all the towns in the region agreed to this same coherent pattern of territorial exchange. Both the layout of the developed area as well as Tocqueville's words reinforce this allegation:

“To keep showing the Arabs and our soldiers that there are no obstacles in the country that can stop us from destroying anything that resembles a permanent aggregation of population, or in other words a town. I believe it to be of the utmost importance that no town should be allowed to survive or grow up in Abd-el-Kader's domains” (Tocqueville, 1988, p. 78).

At this point, it was clear that the strategy of war was added to the embargo in order to colonize the Mekerra plain and build the town of Sidi Bel Abbès.

Choosing and Planning a Site

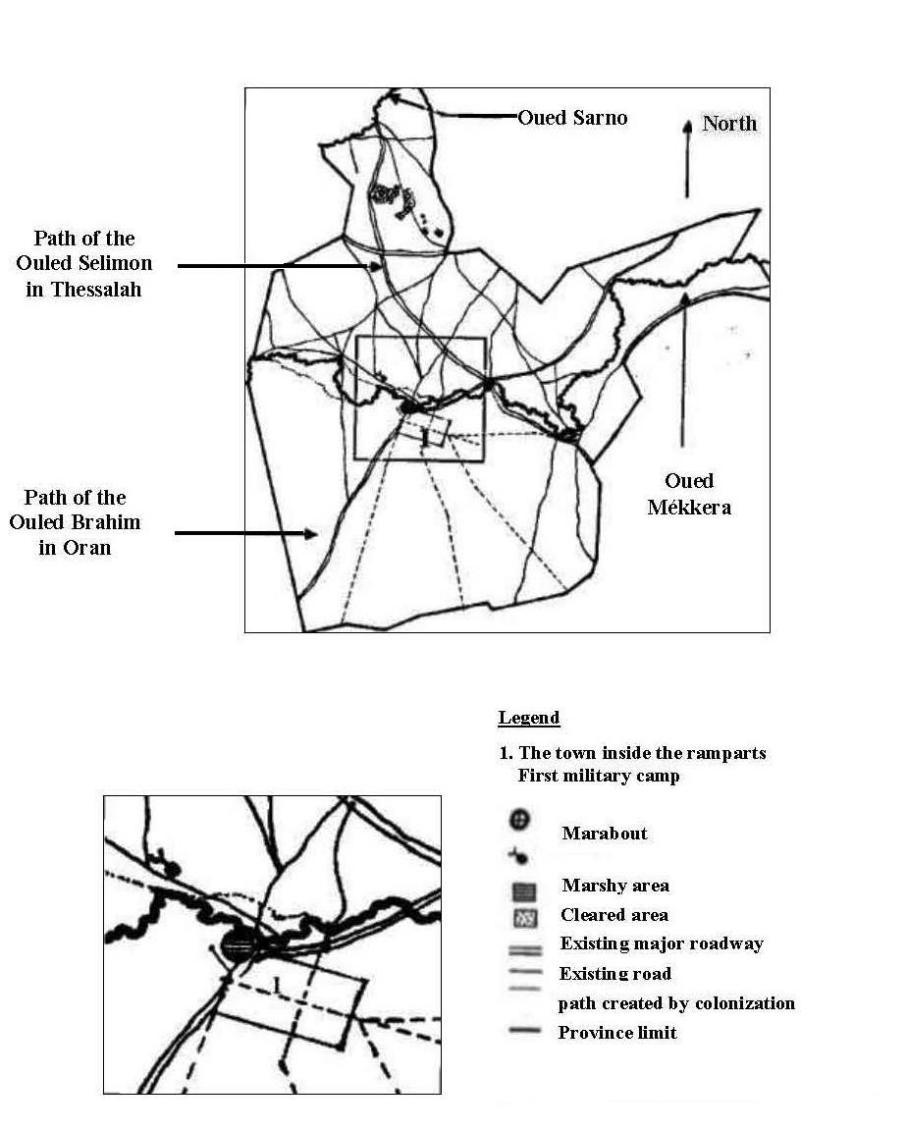

The choice of the site was dictated by its magnitude, a confirmation of the colonizers’ thirst for expansion in all directions (Bastide, 1880). As we have seen, the maneuver, as it is documented in other writings, consisted of neutralizing the region by first occupying the outlying towns of Oran, Tlemcen and Mascara and then setting up a stronghold to extend the operations westwards towards Morocco and southwards towards the Sahara and Africa (Bastide, 1880). The original9 site offered a jagged outline, crossed by the Oued Mekerra (cf., map n°1). It seems to correspond to the territory known as the “Amarna tribe”, the boundaries of which are those of the other tribes in the region, the Ouled Brahim, the Béni Ameur and the Hassasna. The map thus created displays a much contrasted image in terms of the pathways on either side of the Mekerra. In fact, the northern part of the wadi (also known as the left bank in the texts) is characterized by the furrows of numerous roads leading to the strong elements of the site: the wadi, the marabouts Sidi Bel Abbès and Moulay Abdel Kader and then the two major North/South and East/West routes. These two routes are shown on the map as the Chemin des Ouled Brahim in Oran and the Chemin des Ouled Selimon in Tessalah. A particular feature of this area is the presence of cleared land, the existence of which must be attributed to the social actions that originally structured the area. Their position, set back to the north of the Mekerra and closer to the Oued Sarno, raises questions about the logic of occupation that unites a population and its habitat.

The two marabouts near the banks of the Oued Mékerra are about five kilometers apart10. The marabout of Sidi-Bel-Abbès, which has a central position in the site, is close to a major crossroads on the wadi, the importance of which can be measured by the number and quality of the roads that cross it. The marabout of Moulay Abdel Kader, on the other hand, is further away from the major roads and occupies an off-center position closer to the limits of the Hassasna. This distinction in the state of the two marabouts had an influence on the installation of the military camps that were to establish the town. The first of these camps took the name of Sidi Bel-Abbès in reference to the marabout, which was the most striking landmark on the site and also the highest11. The second, known as “the Camp des Spahis”12 (Spahis Camp), was set up near the other marabout. Each one, through his own history, played a part in the development of the town, where the very name of Spahis, which appeared in the toponymy of the area in 1881, is an illustration of the episode which highlighted the presence of the Turks as a rather significant protagonist in the colonization of Algeria.

The Exploitation of the Marabouts in the Colonizing Process

With the colonization of Sidi Bel Abbès underway at regional and local level, we may well wonder why military camps have been set up next to the marabouts, and what might justify it.

Clearly, these places, as it is visible in the trails of the pathways observed, were proof of the existence of a population in the surroundings. Given the motives behind the colonial ambitions, it is clear that the site is strategic in terms of its attractive, cultural and symbolic assets. But the idea of taking an interest in this type of monument can also be explained by calculations aimed at coercing the population by taking advantage of the weaknesses fostered by the Turks:

“The Turks had estranged the religious aristocracy of the Arabs away from the use of arms and the running of public affairs. Once the Turks had been overthrown, that religious aristocracy almost immediately reverted to its role of warriors and rulers. “The most rapid and certain effect of our conquest was to restore to the marabouts the political existence they had lost. They took up Mohammed's scimitar again to fight the infidels and they soon used it to govern their fellow citizens: this is a great fact indeed, one that should be of a particular interest to all those who deal with Algeria” (Tocqueville, 1988, p. 42).

This stage in the colonization of the land involved increasing the pressure to intimidate the population. It also involved multiplying the number of places where troops could be stationed, so that the tribes could be controlled and crushed if necessary:

“At the same time as we were making the troops so mobile, we kept looking for, and found them again, the places where it would be most useful to station them. The war made us identify the most energetic, best organized and most hostile populations. It was next to, or among them, that we established ourselves to prevent or crush their revolts” (Tocqueville, 1988, p. 93).

In the case of Sidi Bel Abbès, the primary target behind the positioning of the camps was to exterminate the troops of Emir Abdel-Kader. Beyond the war and the embargo, the maneuver aimed at exploiting the rift between the different factions of the same religion. In the case of Algeria, the defeated Muslim Turks were going to use this plan to form the Spahis troops:

“It would be superfluous to keep looking for what the French should have done at the time of the conquest. We can only say in a few words that it was necessary first of all to simply put ourselves in the shoes of the vanquished, as far as our civilization allows it; that, far from wanting to start substituting our administrative methods to theirs, it was necessary for a time to bend our own to theirs, to maintain the political boundaries, to take on the agents of the fallen government into our pay, to accept its traditions and keep its usages. Instead of transporting the Turks to the shores of Asia, it is obvious that we should have retained and treated with great care as many as possible; deprived of their Leaders, incapable of governing by themselves and fearing the resentment of their former subjects, they would not have been long in becoming our most useful intermediaries and our most zealous friends, like the Coulouglis who, were somehow much closer to the Arabs than the Turks and yet, almost always preferred to throw themselves into our arms rather than into theirs. Once we would have become familiar with the language, the ways and the habits of the Arabs, after having inherited the respect that men always have for an established government, we would have been free to slowly return to our ordinary life and to convert the country around us to French manners. They (the French) had no idea of the division of tribes. They had no idea of what the military aristocracy of the Spahis was... We have allowed the national aristocracy of the Arabs to be revived; all we have to do now is make use of it” (Tocqueville, 1988, p. 40).

The Road to the Spahis Camp stands out in the landscape, like an indelible trace, linked to the city by the Porte de Mascara, which has contributed to adjusting the war machinery that restructured the territory, giving birth, to the city of Sidi Bel Abbès among other things.

New Towns Modeled to the Design of the New City of Sidi Bel Abbès

Among the executives in charge of the realization of the city, the names of Generals Lamoricière and Bugeaud were top listed. Their mission was in straight line with the colonial strategic and political exigencies of the founding of Sidi Bel Abbès (Adoue, 1927, p. 45). A reminiscence of the creation process of the Roman bastide, which went from being a structure attacking squares to becoming a fortified defensive complex designed to annex a territory. There is a hypothesis to be made here concerning Sidi Bel Abbès which, like the bastides of the late Middle Ages, presents facts reminiscent of the analogies noted by Benevolo about colonial towns:

“It is certainly not a direct relationship, but a significant coincidence of circumstances: in the thirteenth century in Europe as in the seventeenth century in America, there was a problem of colonization and the yearning for a material and mental economy which would produce somewhat similar results” (Benevolo, 1987, p. 210).

In line with the growing interest in the concept of new towns, Sidi Bel Abbès was developed as a comprehensive project in the style of a « ville neuve » (new town).. They were implemented between the end of the 16th century and the last third of the 17th century (Roux, 1997) in France. But, while this type of town was generally intended to ensure the defense of a territory and a nation, in the case of Sidi Bel Abbès, its objectives were more offensive. As we have seen, it was only possible to establish the town after the existing tribes had been forced into exodus, and it then evolved when they were reintegrated as a much needed labour force. Another model for a new town that is reflected in the layout of the space is the one designed by the Spaniards in the 16th century to colonize southern Central America. It does reflect a certain analogy indeed, and it is a well-known fact that it was this model that was applied by the French and the English in the 17th and 18th centuries to colonize the rest of the world (Benevolo ; Léonardo, 1987, p. 319). Sidi Bel Abbès, which was built later, would therefore be an elaborate form of Ville-neuve, combining at least two types and two centuries of construction. The tangible signs of its ancestry can be seen in its localization, size, layout, division of space and the way it is occupied. It is also clear that the town was built at the junction of the main roads in response to a desire to block them, thus imposing a checkpoint to control passage13. This choice of a location at a crossroads “... is almost always linked to a communication facility, either to exploit it... or to block it” (Beaujeu-Garnier, 1980, p. 74). But in the case of Sidi Bel Abbès, there is an obvious interrogation: “why did they choose such a low and marshy plain for the settlement?” We can assume that other, more advantageous factors played a greater role in this choice, especially as strong recommendations had been made for ways to combat unfavorable physical conditions, particularly in terms of draining and drying out the marshes. In addition, among those factors, the proximity of water naturally seemed to have been a determining element in the choice of the town location. Furthermore, Sidi Bel Abbès was part of a project to create a vast agricultural colony, which meant not only welcoming new arrivals, but also encouraging them to stay (Munoz, 1931, p. 52). The issue needed to be resolved by improving the conditions for settling in, in order to mitigate the effects of disorientation and the nostalgia of returning home. In this context, missionaries were to play an important role in evangelizing (Munoz, 1931, p. 152). and providing care. In the projection of the city and its environment, one could read the obvious organization of the area accordingly: the part to be played by the military for control and security, by the urban and rural civilians for colonization, and by the preachers for moralization.

“Some of those means were political or social. Thus, the French had an advantage in claiming at the beginning that they were adopting the customs of the country in order to win the confidence of the inhabitants and, later on, to succeed more easily in converting the Arabs to French manners” (Tocqueville,1988, p. 29).

In the wake of these actions, the town was built by combining the principles of the French Villes Neuves and the Spanish colonial towns, which were also a type of new town. An in-depth study of the descriptions and cartography of Sidi Bel Abbès on the one hand, and of the new towns and colonial cities on the other, provides some insight into the type of town. Their description reveals a twofold image of urban planning that can be transposed to Sidi Bel Abbès. The first relates to the morphology of the type, while the second applies to the use and the “social” organization of the space. The plan of the town in 188114 shows that the area inside the ramparts is divided into two sections by a median transverse axis, with one section reserved for the military and the other for civilians. This configuration corresponds to the organizational mode reflected in the New Town of Vauban's era, which consisted of bringing the garrison life and the civilian population together. The justification for such close proximity was that, for the morale of the troops, “it was more bearable for men and officers alike... if they found a suitable social environment...” (Roux, 1997, p. 35).

As to the built, with a “spirit of geometric regularity” referring to the “pattern of colonial towns”, it is characterized by a chessboard shape and uniformity with no visual hierarchy.

“The grid pattern of the streets seems undifferentiated; the few singular elements - a wider street, a square or an important building - simply interrupt this uniform fabric without inducing an optically enhanced vision of the neighborhood” (Benevolo, 1987, p. 210).

As a result, “...the absence of contrast between town and country” gives an “impression of space through the relationship between the dimensions of the streets and squares and those of the low, modest buildings” (Benevolo, 1987, p. 210).

The houses are almost always single-storey, with tiled roofs. The aspect offered by the sight of the Spanish colonial towns, as reported in Benevolo’s observations, corresponds perfectly to that of Sidi Bel Abbès at that time, a town which can be entered practically without transition... because of the profusion of open spaces in the town (Benevolo, 1987, p. 210).

The Sidi Bel Abbès Project: a Construction Based on the Guiding Rules of the Colonial Doctrine

A project, whatever its level, is the result of political decisions, a system of conventions and the place for know-how. Depending on the context and the site, it brings together and arranges shapes drawn out of a set of ready-made styles and reference models (Pinon, 1994). The reconstruction of the facts for a better understanding of the logic behind the establishment of the town of Sidi Bel Abbès leads us to the conclusion that its location is bound to one fundamental objective: the military control of a territory by undermining the traditions of the existing population. This overriding factor led to the establishment of the first troops encampment, which was to become the thriving hub of the town: “A royal decree of 1847, following the conclusions of General Lamoricière, decided that the military post of Sidi Bel Abbès would be set up as a town and become the chef lieu of the Province” (Adoue, 1927, p. 45). The military context thus created for the colonial cause would influence the mode of composition, the initial structuring of the town and its implementation within the ramparts.The stages in the making of the city, which are part of a shape development program, define the characteristics of this structuring through examination of the instruments of composition: topology, geometry and dimensioning (Pinon, 1994). Their definition makes it possible to explain the reasons behind the physical organization of the space in terms of positions, connections, directions and expanses. The topology, which plays a key role in the orientation of the town, is related to the features of the site: the concavity of the meander on the right bank of the wadi and the longitudinal depression running from west to east, the latter is an asset in allowing water to flow off easily, thus reducing the cost of back-filling operations Maintaining the pre-existing main roads by moving their intersection to the town center, as well as the Thalweg relief which slopes down towards the wadi, will influence the direction of the grid. It proceeds through orthogonality and in accordance with the layout of the major roads that structure the area, linking Oran to Dhaya and Tlemcen to Mascara. This mode of projection of the axes facilitates the phasing of the subsequent interventions that will follow the materialization of the grid. In fact, this type of layout, which is undoubtedly the most widespread, is well suited to the needs of the housing estates (Beaujeu-Garnier, 1980, p. 84).

The geometry of Sidi Bel Abbès is in keeping with the easy design of colonial towns. It has a simple rectangular shape, but shows a deformation at the north-western angle of the ramparts, corresponding to the site of the first military camp, which became a redoubt and from which the town grew. “…From a military point of view, this apparently independent structure necessarily had to be enclosed within the limits of the new town” (Bastide, 1880, p. 28). Nevertheless, it would stand without determining the overall shape, which had to do with the topological axes and the dimension to be given. Thus, the layout of the enclosure was in line with a twofold objective of rationality: that of control, by occupying the plateau for the visibility of the environment, and minimizing the work involved by adjusting irregularities (Bastide, 1880, p. 28).

The dimensioning, while remaining subject to security constraints, depended on the number of strongholds (16) scattered along the perimeter of the enclosure. It also responded to the recommendations made about the use of the town, by allocating each one of its parts a surface area significant enough for an elaborate programme (Bastide, 1880, p. 28)15. Conceived as a garrison town, Sidi Bel Abbès required vast areas to accommodate military activities. However, the concern for the shelter of the surrounding settlers, in the event of an attack, also seems to justify the fact that there are large open spaces inside the ramparts. This situation, which arose during the Si Lala offensive in 1864, had prompted fugitives to take refuge there with their carts, herds and poultry (Adoue, 1927, p. 113). But neither the actions of this tribal chief nor those of Emir Abdel Kader were able to fend off the tide of the colonial conquests in this unequal struggle. The town environment, organized into suburbs to develop an agricultural colony, was essentially made up of farms, enclosures, vast gardens and mansions. Only the “Village-Nègre” reserved for the natives, stood out for its confined shape and its location set back from the entrances to the town. Each suburb thus bears the marks of its social belonging, typical of the segregating measures practiced by the colonial organization. To the north of the city, the railway, an instrument of colonial rule, government and administration, completed the state of affairs to satisfy the needs of the agricultural, commercial and industrial colonization. Sidi Bel Abbès was listed as one of the major military centers, but above all as one of the indigenous markets, the size of which was measured by its extent and its location at the crossroads of nationwide communication routes.

Map 1: Site location of Sidi Bel Abbès based on maps

by Delpy 1851 and Beuzelin 1881

Bibliography

Adoue, L. (1927). La ville de Sidi Bel-Abbès. Sidi-bel-Abbès : René Roidot.

Bastide, L. (1880). Bel Abbés et son arrondissement. Histoire administrative. Oran : Imp. Perrier.

Beaujeu-Garnier, J. (1980). Géographie urbaine. Paris : Armand Colin, Collection U.

Benevolo, L. (1987). Histoire de l’architecture moderne. Paris : Dunod.

Benevolo, L. (1988). Histoire de la ville. Paris : Parenthèses.

Munoz, A.-E. (1931). Sur les pas du drapeau. Oran : Les Éditions catholiques, Heintz Frères.

Reutt, G. (1949). La région agricole de Sidi Bel Abbès. Oran : Imprimerie Heintz Frères.

Roux, A.-de. (1997). Villes neuves. Paris : Ed. Rempart.

Tocqueville, A.-De. (1988). De la colonie en Algérie, Presentation by Tzvetan Todorov – Brussels. Bruxelles : Éditions Complexe.

Notes

1 Chemin de fer de l'Algérie par la ligne centrale du Tell, Algiers, Dubos Frères, 1854. The reference to America is a reminder that the railway was a powerful instrument of colonization.

2 Some views of history glorify colonial action as having created values on virgin soil. General Donop, for example, wrote: “...since it (Sidi Bel Abbès) is the only town in Algeria that has no historical past and everything there was created by the French with the help of foreign labour”, p. 130.

3 According to the definition given by Beaujeu Garnier: Politique et sociale, the concept of “new towns” has spread throughout the world in recent years. This concept corresponds to a desire to create cities where human life is easier and happier: “new housing, facilities, green spaces”.

4 On this subject, see the work of Ainad Tabet Redouane (1990).

5 The locality was known as Dhaya, Bossuet and then Dhaya after independence.

6 Suggestion of M. Laurence in Tocqueville. p. 95-96.

7 82 km from Oran and Dahya, 90 km from Tlemcen, 89 km from Mascara according to the Michelin road map.

8 This article was written on the basis of reported documents, not originals.

9 Map showing the territory of Sidi Bel Abbès on a scale of 1:80,000, dated 1851 and drawn by Delpy, reported by Bastide, (1881).

10 The approximate distance can be read on the scale maps.

11 The topography of the site is made up of very gentle knolls, so the difference in levels between the location of the Sidi Bel Abbès marabout (479) and that of Moulay Abdel Kader (459) is barely perceptible. These two coasts are taken from the 1:25,000 scale 1960 map.

12 The word “Spahi” comes from the Turkish “Sipahi” meaning “Horseman”. The Larousse gives the following definition: A cavalryman in the French army belonging to a corps created in 1834, organized as a “subdivision of the cavalry” in 1841, whose recruitment was in principle based on North African natives.

13 Roux (1997 areports two cases of ville neuve whose purpose was to “block off” or “lock off” a site. These were Mont Dauphin et de Neuf Brisach en France (Antoine, 1997, p. 32-33).

14 Map of Bel Abbès and the surrounding area, based on the work of the Topographical Service by Beuzelin, J.F., ech.1/10000, 1881. This plan is reported by Bastide, L. Op., cit.

15 Details of this programme are provided by Bastide (1880).